Kalush

Kalush is a city of regional significance located in the northwest of Ivano-Frankivsk region (in the Boykivshchyna district). The city's name is likely to be derived from the word "puddle" - a natural salt spring from which salt was extracted in ancient times.

One of the main advantages of the city is its favorable geographical location. A well-developed transportation network connects the city with Central Europe and the West via railways and highways. The highway network connects Kalush with other cities such as Lviv (130 km), Uzhhorod (280 km), and Kyiv (560 km). These and other cities are also connected to Kalush by rail. Within 300 km of the city are the borders with Poland (150 km), Hungary (300 km), Slovakia (300 km), and Romania (240 km), which provides easy access to Central and Eastern Europe.

At the exit to Kopanky, on the left, beyond the bypass channel of the Sivka River, there is a concrete strip of the former airfield, which is now used for racing and exhibitions. 30 km from Kalush, in the city of Ivano-Frankivsk, there is an airport capable of regularly receiving heavy transport aircraft (Boeing 767, Il-76, Il-86).

The city's territory consists of a flat part and Mount Vysoczanka (the district is named accordingly), named after the hero of the Opposition, Semen Vysoczan. The surface of the city is divided by the Limnytsia, Sivka, and Mlynivka rivers. One tenth of the city is covered with forests. The city is divided into industrial and residential zones. The residential area consists of seven districts: two high-rise buildings - the Old Town and New Kalush and five cottage buildings - Banya, Vysoczanka, Zahiria, Pidhirky, and Khotin; it has several markets: the new town - Piatachok and the large Barakholka market, the old town - Rynok market.

It is likely that in princely times there was a settlement on the territory of the Kalush principality, but it is not mentioned in the few surviving written documents from that time, although cartographers record it on maps of the Galicia-Volhynia principality of the 12th-13th centuries. An important factor in the settlement of the region was the salt deposits known in the Kalush region as early as 1387. However, many documents from the fifteenth century have survived. It is from that time that the first written mention of Kalush is found in the twelve-volume Galician Grodzki (Galician province was under the Polish crown at the time) and is dated May 27, 1437. It was about "a trial on the next Tuesday after Trinity with the participation of the royal husband Dragusz from Kalush against Mytko from Kurosh". Since then, Kalush has been mentioned more and more often in various zemstvo books. In 1438, a nobleman named Martyn was the governor of Kalush. In 1440, there is a mention that the King of Hungary and Poland Władysław III Warnenczyk authorized the highest Lithuanian prince and heir to the Russian Mikołaj Parawa to accept the village of Kalush from the hands of a nobleman from the ancient Polish family Piotr Odrowąż (there is no mention that Piotr Odrowąż was the Kalush starosta). On May 1, 1447, Kalush came under the ownership of Mikołaj Parawa from Lubin.

Mikołaj Parawa died together with P. Odrowąż on September 6, 1450 in the battle near the "Red Field". His huge inheritance (several dozen villages in the Lviv, Halych, and Terebovets districts) was inherited by his brother Stanisław from Chodcz. Since 1460, Kalush and its surrounding lands had been owned by the Khodetsky family of ancient Ukrainian origin. This right of ownership was confirmed by the Polish kings. The last starosta of this family in Kalush was Otto Chodetski (1457-1534).

During the XIV - mid-XVI centuries, more than 40 peasant families lived in Kalush. According to the categories, the peasants were divided into free and non-free. The free ones were (as recorded in the acts) "royal people". They owned separate yards and land plots and could leave the village. The second group consisted of unfree or non-free peasants. With the emergence of the lord's manor (mentioned in the acts of 1447), they were enslaved to the lord's court. In 1435, Polish colonization began and Polish law and Polish courts were introduced throughout the region. By the end of the fifteenth century, the remnants of the old Ukrainian veche order were abolished. To consolidate its position, the Polish government encouraged the creation of Roman Catholic parishes. In Kalush, this was marked by the construction of a Roman Catholic church in 1469, which had a hospital and school since 1478.

1490-1492 - peasant uprising in Prykarpattia led by Mukha, in which Kalush residents also took part, and on April 5, 1464, King Casimir IV Jagiellonianchyk presented the Kalush church with one varenyk of salt (saltworks) for use. In 1447, Kalush was mentioned in the acts together with the saltworks as a "zhupa". The first records of the surrounding villages - Nezavyliv, Zarabi, Bratkivtsi, Uhryniv, Dovhe - date from this year. Under the year 1475, the Galician Troy books mention the villages of Rozhniv, Dovhe, Isakiv, Bodnariv, Liutatychi, Tuzhyliv, and Pidhirky near Kalush among other villages.

Until 1549 Kalush remained a village that was part of the Galician starost (county) of the Galician land of the Rus' voivodeship. In 1549, the Polish king Sigismund II Augustus authorized the crown hetman, Belz voivode, and Galician starosta Mykola Seniavsky to found the city of Kalush with the corresponding jurisdiction for self-government. From that year on, Kalush became a "free city" under Magdeburg law with its own coat of arms, which features three salt furnaces on a red background, indicating salt production as the main industry. It also became the center of a non-community starosta, which was separated from the Galician starosta with a group of nearby villages. A city magistrate (city council) was established in the city, and a town hall was built, which was burned down during the National Liberation War (in the early twentieth century a new town hall was built, which was destroyed in the twenty-first century). It was headed by a mayor elected by the citizens. The first saltworks was donated to the newly built church. In 1553, the king transferred the salt works to the nobleman Semiakovsky for his loyal service to the crown. However, he warned that in case of extinction of the family in the male line, the gift would return to the crown, i.e. to the royal property.

1550. The documents mention the lord's malt house. The brewery paid 3 groszy for brewing beer. They made 2 brews a week. They also make yard beer, which is used for the needs of the magistrate. The income generated by these factories is quite high compared to others. By the order of the king, a castle was built on the hill of the city, surrounded by ramparts from the very bottom. The buildings belonging to the castle were connected by underground passages. Kalush, like other cities in Galicia, was turned into a fortress to fight against Turkish and Tatar raids.

According to the lustrations (descriptions of royal estates) of 1565-1566, the city "lay under the mountains above the river Sivka and the second river Chechva (now Mlynivka)," and there were ten salt springs in Kalush and several in the surrounding villages. All chronicle mentions of the Sivka River are related to salt production. Ancient Polish records read: "On the Sivka, they pull salt with a stake. Sivka is a stream over which the city lies." The Mlynivka is a man-made river, 12 kilometers long, the result of many years of work and a lot of people. According to one version, it was dug by Turkish prisoners. In the description of the Kalush starosta for 1565, there is a record that "the peasants of Zahiria had to make gat in the mill."

There was a saltworks near Kalush that used brine from three wells.

1594, July: Tatar raid on Kalush. The city was destroyed (burned to the ground during an attack on Galicia due to miscalculations of the crown command). At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Jakub Sobieski, the father of King Jan III Sobieski, became the starost of Kalush, followed by Lukasz Żółkiewski, and from 1635 by Tomasz Zamoyski. In the early seventeenth century, Ukrainian painter and carver, iconographer Pavlo Gabrielovych (Havrylovych) was born in Kalush. In 1698-1704 he worked under the direction of Job Kondzelevych on the Bohorodchany iconostasis. The processional cross and the iconostasis of the old church in Novytsia are among his works.

From ancient acts we learn about the rebuilding of the town in the early seventeenth century. After the greatest devastation by the Tatars in 1617, 1620, 1621, and a great fire, Kalush was rebuilt in a new settlement. The process of rebuilding Kalush lasted from 1616 to 1630, when the city acquired a new look. The city center with side quarters and narrow streets was part of the fortified part. A rectangular square was formed in the center, in the middle of which a wooden town hall was built, which was replaced by a stone one in the middle of the seventeenth century (in the fall of 1648, during the Khmelnytsky period, it burned down). The town hall was surrounded on all sides by shops where craftsmen sold their goods. Behind the fortified city center were the Kalush suburbs, called Halych, Lviv, and Dolyna. There were Panska, Zamkova, Kostelna, Halytska, Pid Valom (now Pidvalna), Za Valom, and Na Hrebli (On the Dam) streets. The brewery was located on the outskirts of the city, and Zahiria was a suburban village at the time. In 1565, salt was produced in 3 bathhouses with 4 towers, which were rented by two local burghers. One belonged to the starosta and one to the church. In 1569 in Kalush, in the center of the city, there were two houses, one of which was occupied by the local starost and the other by a cartman. In the middle of the sixteenth century there was a "vodka tavern" in Kalush. There was a mill on the Chechva river, where 2 flour wheels worked, and the 3rd one was a kneading mill. There were church buildings both in the city center and in the suburbs. The Catholic church, built of spruce wood, stood near the castle wall in the city, and the main church of St. Michael stood on the other side of the castle wall.

The people of Kalush made great efforts to free themselves from Polish rule during the liberation war of the Ukrainian people led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky. In the fall of 1648, a Ukrainian self-government was established in the city, headed by Mayor Hryts Volykovych. Ivan Korytko (Hrabivsky), a priest from Hrabivka, led an insurgency in 20 villages of the Kalush district, in which up to 5,000 people participated in October-November 1648. Having liberated the Kalush starosta from the Polish invaders, the rebels under the leadership of Ivan Korytko successfully operated in the Dolyna region, where they united with the army of Semen Vysoczan. In December 1648, the starosta forester Danylo Makovsky, taking advantage of the confusion among the rebels, unexpectedly captured Kalush, imprisoned the leaders of the uprising led by Ivan Korytko, and restored the old noble-patrician government in the city. The leaders of the uprising were imprisoned in chains and thrown into the castle fortress. Subsequently, the Polish authorities exempted Danylo Makowski's estate from taxes and granted him a portion of the city's land. In the same month, in Kalush, the gentry killed more than 200 peasants who participated in the uprising. The gentry dealt with the thirteen leaders of the uprising in the most brutal manner. The register of the starosta's subjects, compiled by Danylo Makovsky, states that "Colonel Ivan Hrabivsky, the burgomaster of the new Ukrainian government, Hryts Volykovych, rayon resident Ivan Ovsianikov, Fedir Kravets, Yurko Kobelik were killed on a pile, and Protsko was 'quartered. Pip Kostyk, Les Oryshchak, Fedko Shvets, Matviy Shvets, and a burgher Maletsky were "tortured to death," and a burgher Petro Kozak was "shot." 1649 - The General Tribunal of Lublin sentenced the participants of the insurgency in the Kalush district to death "by stabbing with a sword." The sentences were carried out in 1650.

- June 1649 - nobleman Jan Sobipan Zamoyski began to serve as starosta in Kalush, who in 1655 fully acquired the rights to the Kalush starosta and called himself "his own lord in Kalush." After him, the Kalush starosta was given to Jan Sobieski. In 1703, the Kalush starosta was transferred to Stefan Potocki, and later to Stanisław-Ernest Denhoff.

- On October 16, 1672, Jan Sobieski's troops, including Kalush residents, defeated a large detachment of Tatars under the command of Khan Selim Giray. A large number of people (including more than 1000 children) were liberated from captivity. King Sobieski built an orphanage for them in the city.

- In 1675, the Tatar hordes were defeated near Kalush for the second time by Polish troops led by Kyiv voivode Andriy Potocki, the founder of the city of Stanislaviv.

- 1731 - a wooden church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (later rebuilt) is built in the city.

- 1765 - there were 64 large and 194 small Christian houses in the town (those belonging to Poles and Ukrainians). There were 62 large and 73 small Jewish houses. At this time there were 2 churches and a Z-church in the town.

- In 1767 Kalush suffered a large fire that occurred spontaneously. In 1770, a cholera epidemic depopulated the town. In the surrounding villages there are mass graves of those who died during the epidemic. In Kalush and its suburbs, almost half of the inhabitants of Kalush died of the "pestilence."

- In 1771, Kalush salt miners had 12 wells. It employed 33 craftsmen (including 5 coopers). Near the saltworks there was a smithy where iron was smelted and the iron for the saltworks was produced. Later, the Austrian government introduced a state monopoly on salt and forbade private use of the earth's mineral resources.

Church of the Nativity

One of the oldest churches in the city, the Church of the Nativity, dates back to the fifteenth century. In the Middle Ages, Ukrainian burghers, artisans, merchants, and ordinary people from the suburbs of Kalush gathered around it. In the early seventeenth century they organized a church brotherhood. The mother church of the Nativity stood on the other side of the castle in the city itself on long-dedicated ground. It had a bell tower with four bells. Near the church was an ancient cemetery fenced with a wooden raft. In the 18th century, the church had church books from old prints: a printed Gospel and a service book published in the printing house of the Lviv Stavropegian Brotherhood. There were also two other prayer books, one of which was published in the Univ printing house. In addition to these publications, other old printed books were kept in the church: two triodices, a trifolium, an octoeuch, a chasos, and three liturgical books. There were highly artistic images transferred from the old church. Probably, in the Church of the Nativity under the bell tower there was a separate chapel of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The kyvot in the church was of "carpentry" and unpainted. A wooden cross stood on the throne. On the sides of it were wooden or zinc lanterns. All the villages of the Kalush deanery had two or even one of them, and the Church of the Nativity had 9 such lanterns, the ninth being a triple lantern. There were also two censers, one of them with silver chains. The faithful hung various gifts on the icons. In early 1740, there were 6 silver crowns, 6 similar plates, 4 laces of small corals, and 4 "jedwabniczki" on the vicarage icons in the church. The church had 6 felons, 2 banners, and a beautifully wrapped Gospel.

To this day, we have an altar from this church, which is kept in the church of St. Archangel Michael in Kalush. A brief description: it was made in the eighteenth century in the Western Baroque style. On the altar there are images of the late period: "The Nativity of Christ" and "The Sacrifice of Abraham". However, some features of the early icon can be felt in them. The altar is crowned with carved sculptures of God, the Creator of the Universe, Saints Cyril and Methodius, and an angel. The history of the church ends at the end of the 18th century. This is probably due to the construction of the Church of St. Michael the Archangel in 1771.

Kalush Castle

Few Kalush residents today know that there was a medieval castle in the city, which was called the starosta castle in the deeds, since in 1549-1778 the Kalush non-grassland starosta was headquartered here. Not a single trace of the wooden or stone castle structures has survived. At the beginning of Austrian rule, the Kalush castle was demolished. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the stones were partly used by the city magistrate and partly by the townspeople for their own needs. Unfortunately, the architects, artists, and Austrian rulers of the time did not leave us any plans, schemes, or drawings of the castle.

Kamil Baranski suggested that a defensive castle existed in Kalush as early as the 13th century, when Hungarian miners appeared here as specialists. Since that time, he believes, the suburb has been called Banya, and the city has received a Hungarian cross over a salt furnace in its coat of arms. However, the Hungarians were nomads, and at that time Hungary itself did not have such industries and such specialists, and the fictions about Hungarians were used by the Poles to silence the real Ukrainian history. And the word banya is not Hungarian, but Old Slavic and is characteristic of all Slavic languages, and even penetrated Italian, and from there returned to Ukrainian as "mud."

We first come across a reliable description of Kalush Castle in the royal lustration of 1661. It states that the castle has an entrance to the city, where the castle gate is located, in which there is a room that is a dining room with a pantry. Then there were 8 rooms with rooms. There is a large cast-iron cannon, 2 iron cannons, and 10 hooks. Several rooms were also located at the exit from the castle to the walnut garden. On August 1, 1636, Queen Marysienka Sobieska and Chancellor Andriy Zaluski visited Kalush Castle to participate in the commissioner's trial of infidel Jews. Lustration of 1771 - The city castle is surrounded by a rampart on the eastern side, which has a fence. On the western side, the fence is on stone foundations; to the south, from the cemetery, the castle was fenced with brushwood; to the north, with a fence with a roof. The entrance gate to the town is made of stone. It has a house for the guards. On the top of the castle there is a residence with a porch around it. All of the castle buildings were connected by underground passages, the remains of which existed even before the beginning of the twentieth century. The place where the post office used to be in the days of Austria and Poland was once the royal hunting ground.

As part of the Habsburg Empire

During the first partition of Poland in 1772, Kalush, along with all of Galicia and part of Volhynia, came under Austro-Hungarian rule. The city of Kalush was a provincial town. It was subject to the administrative and financial regulations of the Stryi district.

On September 25, 1772, the Kalush community, which gathered near the church of St. Valentine, read out the universal of Empress Maria Theresa on the accession of the region to Austria-Hungary.

Due to the impassability of the road, Austria built the state Carpathian highway through Kalush. It ran from Slovakia through the Yabluniv Pass and then through Zhyvets, Novyi Sanch, Yaslo, Sambir, Stryi, Dolyna, Kalush, Stanislaviv, Kolomyia, and on to Chernivtsi[10]. Soon, the "post office" began to run along these roads, and then stagecoaches; the so-called fast or ordinary ones, which were used to travel for quite a long time.

Craftsmen and specialists from various industrial sectors started producing salt, nitrate, potash, etc. here.

During the Polish rule (until 1772), Augustus Oleksandr Czartoryski and Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski were the headmen of Kalush. After them, Kalush passed into the possession of Crown Prince Stanisław Lubomirski, who immediately banned private saltworks (in 1782 Lubomirski officially received the Kalush starostvo from the "treasure of Austria"). In 1783, the Kalush private saltworks ceased to exist, and a state-owned one began to operate.

In 1784, the German settlement (colony) of New Kalush was founded near Kalush (in 1881, 577 inhabitants lived there).

It is known that in 1786 a local school with German language instruction began operating in the city, and in 1811 a two-class folk school with 50 students was opened. In 1832, in addition to the public trivial school founded by the state, there was a parish school at the church of St. Michael (which is recorded in sources as early as 1782). As early as 1847, Kalush had a four-grade boys' school and a one-grade girls' school.

In 1790, the city cemetery was founded, and in 1792 the wooden church of St. Andrew was built in the city, located in Zahiria.

In May 1804, during the deepening of a mine near Kalush, the so-called "bitter" salts, cainite and sylvinite, were found. Economic structures changed, and in 1867 a joint-stock company was founded to develop potash deposits. Two years later, a factory was built in Kalush to process potash ores.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, in 1808, the Felchynsky brothers, residents of Kalush, founded a factory in Kalush that cast the famous bells[12][13]. It was first located on King Jan Sobieski Street (today it is the area of the magistrate's office and secondary school No. 1). Felczyszky's bells won the Grand Prix at world exhibitions in Liège, Belgium (1927) and Paris (1928). And 12 whistles under the name "Harmony" were cast for one of the cathedrals of the United States.

From 1811 Kalush was part of the Stanislaviv state administration, which covered the present territory of Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil regions. In 1850, as part of an administrative reform, the Kalush district (betsirk) was formed, which included the Kalush, Voynyliv, and Zhydachiv judicial districts. In 1867, another reform changed the configuration of the district, which has since included 90 villages.

On January 1, 1875, the Archduke Albrecht Railroad was put into operation and the Kalush station was opened.

The People's Bank was founded in Kalush in 1876.

After the abolition of serfdom in Galicia in 1848, democratic institutions were introduced, children were allowed to be taught in their native language, and reading rooms were opened. In 1884, Ivan Franko visited Kalush and gave a lecture on Samiilo Kishka at the People's House during a literary and artistic festival (now the museum-house of Ivan Franko's family is located in Kalush). At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a branch of Prosvita was established in Kalush.

The choir and orchestra of the reading room "Early Dawn" organized in 1890 was very popular in the city. It consisted of 21 people who sang and played wind instruments. In 1893, a 2.5 km long city water supply system was laid from Limnytsia through Khotin and Zahiria. In 1909 a cinema was opened in Kalush.

The natural gas discovered in 1910 during drilling was used to illuminate the city in street lamps, and since 1933 - for heating. In 1912-1913, an oil well was laid near the city of Kalush, but instead of oil, deposits of combustible gas were discovered[16]. It was not used for a long time, then it was used to heat a potash mine, boiler plants in Boryslav and Drohobych[16]. Attempts were made to use the gas for heating the premises as well.

In 1912, the first power plant was built in Kalush to facilitate the extraction of potassium salts. Later, the electricity it produced was used for the needs of the city.

Architectural monuments

In total, there are 45 architectural monuments of local importance in Kalush and its surroundings. The most important historical and architectural monuments of the city include:

- St. Valentine's Church (1844) - built in the Neo-Gothic style, the church is a real business card of the city.

- Church of St. Michael the Archangel (1910-1913)

- The People's House (1907) - built in the Art Nouveau style with many elements of classicism.

- The residential building at 22, Heroiv Square (XVII-XVIII centuries) is one of the oldest in the city.

- House of Sokil Society (concert hall of Kalush College of Culture and Arts) - (mid-nineteenth century)

- Church of St. Andrew (1792)

- Kalush school No. 1 (early XIX century)

- The former Jewish synagogue is now the Kalush Regional History and Local Lore Museum (1930), built in the style of constructivism with elements of modernism.

- The Museum-House of Ivan Franko's Family is also open.

Nowadays, the Stepan Bandera Ice Palace in Kalush hosts hockey tournaments, where the Kalush team plays. It is also open to the public.

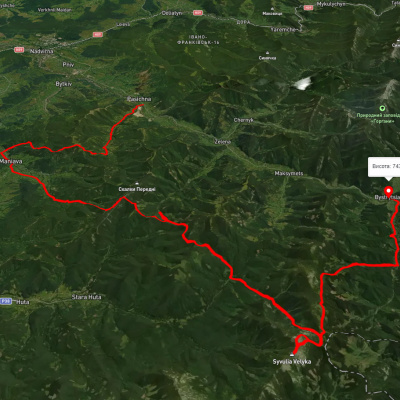

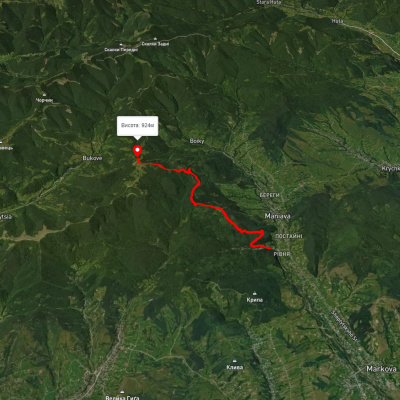

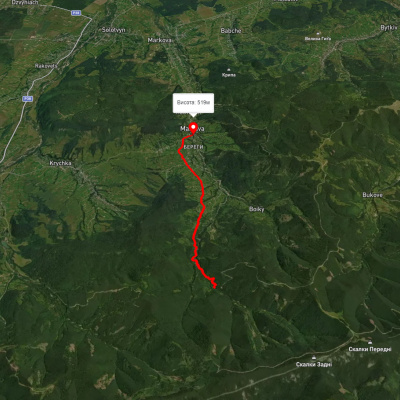

Які туристичні (пішохідні) маршрути проходять через/біля Kalush?

Пропонуємо пройти такі туристичні (пішохідні) маршрути через/біля Kalush: с. Пасічна, через с. Манява, Манявський вдсп., г. Велика Сивуля до с. Бистриця, с. Манява - пол. Монастирецька, с. Манява - вдсп. Манявський, с. Гута - с. Пасічна, Гута - Погарчина, с. Стара Гута – г. Ігровець – с. Стара Гута