New settler

On the wide flat terrace of the left bank of the fast-flowing Prut River, where the small Rokytnyanka River flows into it, lies the town of Novoselytsia, a village in Bukovyna, the district center of the Novoselytsia district of the Chernivtsi region. It has a picturesque forest-steppe nature with a mild climate and is home to kind and hardworking people. It is located 30 kilometers east of the regional center. Novoselytsia is crossed by the highway from Chernivtsi, which branches in the town to Chisinau-Odesa and to Khotyn-Khmelnytskyi-Vinnytsia-Kyiv, and the Chernivtsi-Chisinau-Odesa railway line, which branches to Kyiv from the station Oknytsia. The earliest written mention of Novoselytsia dates back to 1456.

According to research, the area between the Prut and Dniester rivers, where Novoselytsia is located, has been inhabited since ancient times. Stone tools of ancient man (scrapers, axes, hammers, choppers, cutters) dating back to the Stone Age have been found in many places in the area. Settlements of Trypillian (IV-III millennia BC), Komarivska (XV-XIV centuries BC), Cherniakhivska (III-IV centuries AD) and other cultures, as well as cultures of the early (V-first half of the XIV century) and late (second half of the XIV-XVIII centuries) Middle Ages were discovered here.

The first known people to inhabit the lands between the Danube and the Dniester were the Goths (of Trakish origin). In the first century AD, the Dacians, who came from the Rhodope Mountains, appeared next to them. During the period of great travels of various nomadic peoples, the territory of the region was crossed by Goths, Huns, Hepids, Avars, Ugrians, Pechenegs, and Scythians. Later, in the fourth century, a group of Slavic tribes, the Ants, formed a state union over a large area, which later formed a number of tribal associations. The territory of the middle and lower interfluve of the Dniester and Prut rivers in the eighth and first half of the ninth century was occupied by the Slavic tribes of the Tivertsi.

For more than 200 years (855-1100), the territory of the region was part of the early feudal state of Kyivan Rus, and from the twelfth century it was part of the Principality of Galicia and Galicia-Volyn (from 1199). The Mongol invasion led to the decline of the Russian principalities. The lands of the weakened Galicia-Volhynia principality were seized by Hungary. Wallachian feudal lords were appointed as governors of our region.

In 1359, the Wallachian feudal lords, taking advantage of the population's dissatisfaction with the existing power of the Hungarian king, rebelled. Hungary was forced to recognize the existence of the Wallachian Moldavian principality, which included the territory of the region. It was during this period that the Wallachians, the ancestors of Moldovans and Romanians, migrated to Bukovyna. A number of settlements were founded, the first mentions of which, including Novoselytsia, date back to the XV century. This indicates that this or that settlement was founded much earlier.

For the first time Novoselytsia was mentioned in documentary sources in 1456 under the name "Shyshkivtsi, where Yurii's court was, on the Prut". Later, in the documents of 1617, the village is mentioned as "Shyshkeuts near the Prut, now called Novoselytsia". The name Novoselytsia indicates, in particular, that it was not just a name change, but the emergence of a new settlement near the deserted Shyshkivtsi.

The first small settlement appeared here near the Prut River, on its floodplain terrace. A small wooden church stood on the northern outskirts of the settlement. Over time, it collapsed, and a chapel was built in its place. Some items from the old church with inscriptions in Old Slavonic were moved to it. Judging by these items, we can conclude that the old church was built around the end of the 16th century. After the new church was built in 1858, the chapel was dismantled. Now the site of the old church is located at the very bank of the Prut river, close to the southern outskirts of Novoselytsia, where the remains of the church cemetery were preserved until recently.

With the destruction of the left bank of the terrace on which the village was located, the population retreated from the river to the north, closer to the road, a land trade route that in the XII-XIV centuries ran along the Prut River valley from Halych, the capital of the Halych and later the Halych-Volyn principality, to Byrlad. Thus, the city owes its birth and development to this Byrlad road. The houses here were log or clay-built, with thatched or reed roofs.

In the XVII century, the western part of Novoselytsia was settled. A settlement called Dolyshni Stroyintsi emerged across the Rokytnyanka River, and even further west - Horyshni Stroyintsi (later Hohulyany). Dolyshni Stroyintsi gradually merged with Novoselytsia and became known as Selyshche. The small settlement, which arose at the junction of territories inhabited by different peoples, was gradually settled by representatives of various ethnic groups, including Ukrainians, Moldovans, and Jews. This, of course, affected the national composition of the city's current population, where representatives of different nationalities live together as a friendly family. The inhabitants were mainly engaged in farming and cattle breeding, and were involved in trade and crafts.

In 1514, the lands of the Moldavian principality were conquered by Sultanist Turkey. Only as a result of the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-1774 was the territory of the region liberated from the Turks. After the conclusion of the Kuchuk-Kainarjia Peace Treaty between Russia and Turkey in 1774, Novoselytsia became a border post and was divided into two parts: the western part was occupied by Austria, and the eastern part remained under the Turks. The border in the town between the two states ran along the Rokytnianka River.

The lands of the western part of Novoselytsia were seized by the Austrian baron Zota. The peasants were forced to work in the baron's fields from dawn to dusk, to care for his cattle, and to build his estate and outbuildings. Some of the peasants who remained free became serfs of the Radivtsi bishopric in 1782, and two years later they were transferred to the Horecha monastery. In 1788, the monastery exchanged the Novoselytsia lands for the lands of the Moldovan landowner Cantacuzino. Thus, the Novoselytsia lands and the peasants assigned to them became the property of the latter. In eastern Turkish Novoselytsia, the lands belonged to Moldovan landowners from the Sturds family. In 1804, for example, boyar Ivan Sturdza owned an estate with 204 peasant yards in Novoselytsia.

As a result of the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-1812, Russian troops won and liberated the eastern part of Novoselytsia from the Turks. In 1812, according to the Bucharest Peace Treaty, this territory was annexed to Russia and became part of the Khotyn district of the Bessarabian province. The western part of the settlement remained under the rule of the Austrian Empire. Later, there were cases when the border river Rokytnianka changed its course on the lands of the villages adjacent to it, which caused misunderstandings and disputes. This problem was solved by a mixed international commission that was created to restore the state border.

Customs offices were opened in the Russian part of Novoselytsia in 1817 and in the Austrian part in 1847. They controlled the movement of goods and people along the Prut River and the dirt road connecting Northern Bukovyna and Bessarabia. They built solid buildings for the border and customs administration, barracks, and warehouses. In the early nineteenth century, crafts and trade developed in both parts of Novoselytsia, and industry was born. By 1828, the eastern part of Novoselytsia already had 2 shoemakers, 2 tailors, 3 furriers, 2 wheelwrights, a weaver, and a blacksmith.

The favorable geographical location, the development of crafts and trade led to the opening of a fair in the 40s of the XIX century. It was then that Novoselytsia began to be called a town. A network of artisans grew, bakers, butchers, carpenters, coopers, soap makers, plasterers, tinkers, hatters, barbers, etc. appeared. A number of small shops appeared.

In 1850, the construction of a gravel road from Chernivtsi through Novoselytsia to Lipkany was completed and a ferry crossing the Prut River to Moldova was built. This contributed to the further development of crafts and trade, as well as the settlement and development of the town. From 1849 to 1859, 20 houses, a pier, and several water mills were built here. This was noted in the documents of 1860: "The town of Novoselytsia is of great commercial importance. There is a warehouse of timber that is floated down the Prut. From Novoselytsia, the timber is transported overland to the Dniester, and from there it is floated to all places in Middle and Lower Bessarabia. The main trade route is Novoselytsia, Khotyn, Chisinau... Novoselytsia is the main point through which cattle and leather are sent to Austria."

The Austrian press of the time wrote about the Chernivtsi-Novoselytsia road: "...this is the route that carries all trade and passenger traffic with Russia. Thousands of oxen are driven to Vienna every year, and thousands of wagons of grain, hides, etc. are transported along it. This road serves as a transit road for the southern and northern parts of Russia." As a large settlement, Novoselytsia became the administrative center of the Novoselytsia volost of the Khotyn district in 1861. At that time, the town was rapidly developing. While in 1862 there were only 300 houses, in 1870 - 342, in 1875 there were already 509 houses, and 3031 residents lived there, including 1549 men and 1482 women.

Most of the land in the new settlement belonged to the rich. Count Sturdza, for example, took over the best lands of Novoselytsia, the villages of Marshyntsi, Tarasivtsi, Koteleve, and others. In addition, he owned several shops, a distillery, 10 water mills, a hotel, and 281 peasant households with 1405 inhabitants in Novoselytsia. The landowner brutally exploited his subordinates. In May-June 1870, the peasants of Novoselytsia and the surrounding villages refused to perform natural duties and did not go to work on the landowner's fields. Because of this, two hundred Cossacks were sent to Novoselytsia and brutally suppressed the uprising. Subsequently, after his death, the boyar's lands were transferred to his relatives named Donych.

In 1870, Novoselytsia had a distillery, a steam mill, two tanneries, and an oil mill. These were small artisanal enterprises where production was done by hand. In 1880, the two tanneries, owned by the townspeople Moishe Eidelman and Anchel Goldenberg, employed only five freelance workers who processed 2,500 skins a year by hand. Sura Shapir's candle and soap factory, with an annual production of 50 poods of soap and 100 poods of candles, employed only two freelance workers. With the development of capitalism, the owners of the town's enterprises partially mechanized production. The merchant Mordko Kleitman, the owner of the oil mill, installed a steam engine, two mechanical presses, and laid a water supply system.

The construction of the Chernivtsi-Novoselytsia railroad in 1884 and the Novoselytsia-Oknytsia-Zhmerynka railroad in 1892 was of great importance for the development of the economy. As a result, in November 1893 the Bukovyna railways were connected to the Russian southwestern railways. Novoselytsia became an important transit point. In the middle of 1899, a customs outpost was opened north of the customs office, at the junction of the Russian southwestern railways with the Austrian railways.

The main flow of goods and passengers from Northern Bukovyna to Russia, in particular to Bessarabia, Podillia, Naddniprianshchyna, and Kherson, was carried out through the customs office and customs outpost. From Northern Bukovyna and Galicia, timber and timber products (boards, lathing, rafters, shingles, shingle, tannic bark), as well as salt, yeast, carpets, cloth, cotton and woolen goods, machinery, tools, and watches were mainly sent. In the opposite direction, livestock (cows, oxen, pigs, sheep, goats), rawhide, wool, live poultry, eggs, feathers, grain (corn, rye, barley, oats, buckwheat), vegetables, and fruits were exported from Bessarabia.

The development of transportation contributed to a rapid increase in the number of freelance workers, particularly in the repair depot and at the lumber yard.

In 1910, the 14th volume of a large collective work under the common title Russia was published in St. Petersburg. Chapter eight of this volume reads: "One mile south of the station, on the very border with Bukovyna and Moldavia, at the confluence of the border river Rokytnyanka into the Prut and on the postal route, is the volost town of Novoselytsia, which has about 5900 inhabitants, mostly Jewish (about 3900) souls, an Orthodox church, a Jewish synagogue, several houses of worship, a school, an infirmary, more than fifty shops, several small factories (tanneries, soap factories, etc.), and more. There is a customs office here, a storage facility for timber that is floated down the Prut." The book notes that Cossacks live here, among those who came here in the sixteenth century with Hetman Ivan Svirhovsky to help Wallachians in the fight against the Turks and stayed here.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, more than 90% of the population were illiterate and illiterate. In the Austrian part of Novoselytsia, a four-grade school with German as the language of instruction was opened only in the 1980s. There were no Ukrainian schools here. In the Russian part of the town, there was a parochial school with 12 children and a zemstvo school with 65 students. There was only one private library in the entire town, and the owner charged money for its use.

When the First World War broke out, Novoselytsia found itself in the center of hostilities between Russian and Austro-Hungarian troops. Russian troops advanced and retreated, so the town changed hands. The hostilities caused great devastation to the town: many houses were burned or destroyed, gardens were cut down, fields were trenched, and a large part of the population was evacuated.

In the summer of 1916, Russian troops under the command of General A.A. Brusilov began to break through the Austro-Hungarian front. It was from the area of Novoselytsia that the military units of the 8th Army began their offensive against Chernivtsi. Bukovyna was occupied by Russian troops. War-weary soldiers greeted the news of the February Revolution with enthusiasm. They began to create their own democratic bodies, the Councils of Soldiers' Deputies. In March 1917, such a body was established in Novoselytsia.

After the October Revolution of 1917, in January 1918, the IV Peasant Congress of the District Soviets was held in Khotyn, which was attended by representatives of Novoselytsia. The congress proclaimed the establishment of Soviet rule in the Khotyn region. The peasants were given the land confiscated from the landlords. However, on February 28, 1918, Austro-German troops captured the Khotyn district, including Novoselytsia. The peasants were ordered to return the landowners' land, livestock, and equipment. In early November 1918, the Austro-German troops retreated under the blows of revolutionary forces. But soon that month, Romanian troops invaded Bessarabia and Bukovyna. In January 1919, the famous Khotyn uprising broke out, in which residents of Novoselytsia took an active part. The rebels fought bravely for twenty days. A group of Romanian troops, fleeing from them through the territory of the Novoselytsia district and the city, robbed the population and shot civilians. On the outskirts of Novoselytsia, the rebels defeated the border guard unit, surrounded two Romanian regiments, and took away the loot from the fleeing. But the forces were unequal, and the rebels were forced to retreat.

In the occupied territory of the region, the boyar-Romanian invaders established an occupation regime. From the first days, they launched a fierce campaign against the Ukrainian language and culture. It was forbidden to speak Ukrainian in government offices, courts, schools, and even churches. They began Romanizing the population, renaming settlements and streets. Before the Romanians arrived, Novoselytsia had streets named Tsentralna, Khotynska, Sadhirska, Lypkanska, Generalska, Adjutantska, Poshtova, Tsyhanska, Banna, and others. The streets were now named Stefan cel Mare, King Ferdinand, Prince, Dragos Vode, Alexander Kuza, and others. Novoselytsia itself became known as "Knowa Sulica" (New Sulica).

The peasantry was ruthlessly robbed, and heavy taxes fell on their shoulders. The best lands in Novoselytsia became the property of large landowners. The wealthy Tsybulskyi owned 300 hectares of land, and the landowner Romashkan owned 200 hectares of arable land and 200 hectares of meadows and vines. At the same time, all peasant households in the settlement had only 300 hectares of land.

By the early 20s, the town's population had grown to 10,000 residents, mostly of Jewish nationality. In those years, mass emigration of Jews to Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, and Chile began. Engaged in business, they quickly accumulated capital, staying there or returning. In 1920, a distillery was built in the western part of the city on the estate of the landowner Kraus, which employed about 50 workers. A Jewish entrepreneur Abram Stein built a sawmill on the banks of the Prut River, the so-called trachka, which burned to the ground in 1924. A starch factory was built near Rokytnianka. In 1922, there were 27 taverns, an Orthodox church, and 10 synagogues in Novoselytsia. In 1925, German entrepreneur Ludwig built a steam mill and a small power plant with a capacity of 45 kilowatts.

In his book Memories of Bessarabia, published in 1993 in Jerusalem, a native of Novoselytsia, Max Roitman describes Novoselytsia in the 1920s in detail. He writes that the town was planned in the form of a rough grid: three streets long and six across. It stretches from the Prut River to the railroad. Most of the houses here were made of clay, covered with straw or shingles. Only the rich lived in the central part of the town in brick houses with luxurious furnishings, carpets, sofas, and pianos. There was no electricity or sewage in the town. Only the central road was covered with gravel, and the sidewalks were covered with boards. There were ditches along the road for water drainage.

The town's residents were engaged in crafts, trade, and entrepreneurship. One entrepreneur set up a salt factory, grinding salt with the help of a horse, another produced sugar from sugar beets, and a third made wheel rims. There was also an oil mill, a soap factory, and a sawmill. Thus, Novoselytsia was an ordinary provincial town. And yet, thanks to its position, it had something peculiar that helped the residents overcome boredom: the Prut River, a source of pleasure and a place to spend their free time, railway stations in the Russian and Austrian parts of the town, from where trains ran to nearby Chernivtsi, where they could establish business contacts, consult a doctor, and wander around the shops and cultural institutions.

In 1931, a poultry slaughterhouse, the present-day poultry processing plant, was built in the western part of Novoselytsia, which belonged to the Paserya joint-stock company. Buyers brought poultry here from different parts of Bessarabia and Bukovyna. The processed products were mainly shipped abroad - to Austria, Germany, Italy, England, and Palestine.

On June 26, 1940, the USSR government sent a note to the Romanian government about the return of Bessarabia and the transfer of the northern part of Bukovyna to the Soviet Union. On June 28 of the same year, the Red Army entered the city. Soviet rule was established here. Industrial artels of shoemakers, tailors, and hairdressers were organized. The newly created industrial plant united an oil mill, a furrier's shop, a limestone factory, a soap factory, a candy and halva shop, and a stone shop. Skilled carpenters who had previously worked for entrepreneurs formed the Chervonyi Meblevyk artel. The production facilities of the tannery were expanded, and construction of a brickyard began. A machine and tractor station was launched in Novoselytsia.

In March 1941, 45 poor and middle-class farms in Novoselytsia united into the Chkalov Agricultural Artel. It had 100 hectares of land, 11 horses, 5 heifers, 10 sheep, 350 chickens and 50 ducklings, an apiary of 14 bee colonies, and some agricultural implements. A ten-year school with Ukrainian as the language of instruction, a junior high school, and two elementary schools with 1295 students were opened in the town. In a short period of time, the hospital was expanded to 100 beds, and a district health department, polyclinic, dispensary, children's consultation, and sanitary inspection were opened. A cultural center, a cinema, and a house of pioneers were opened in the district center.

The German-Romanian invaders caused great damage to the town. Its center, depot, sawmill, tannery, and power plant were destroyed, and about 560 houses were burned. The town's residents cherish the memory of 218 Novoselsk residents who gave their lives defending their homeland. On the main street there is an obelisk to the fallen soldiers with their names engraved on it. And in the park of culture and recreation there is a mass grave where the soldiers-liberators sleep in eternal sleep. Immediately after the liberation of the town, its reconstruction began. Novoselytsia residents love their town, which will become even more beautiful in the near future.

There are more than 90 streets in Novoselytsia. Each of them is unique. The names of many streets have a breath of history in them. Many of them are named after people who are directly related to the town. The residents of Novoselsk honor the memory of their liberators. Relatives of Heroes of the Soviet Union E.K. Kremlev and O.M. Ptukhin, Senior Lieutenant G.I. Koberidze and other fallen Soviet soldiers who are buried in Novoselytsia have repeatedly visited the town.

Despite the economic difficulties that befell our state at the beginning of its formation, the people of Novoselytsia made every effort to stay afloat, as they say. There have been achievements and setbacks along the way.

Novoselytsia is becoming more beautiful and well-maintained. A monument to Taras Shevchenko was unveiled on the central square. The pedestrian paths of the town's main street are covered with paving slabs.

The network of private shops, cafes and bars has expanded significantly. Elegant "buses" replaced the buses that used to run between Novoselytsia and Chernivtsi, as well as between the town and the villages of the district. The town lives, develops, and grows stronger.

AUTHORS: Oleksiy Ivanovych RYDYUK, honorary member of the Ukrainian Society for the Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments; Yosyp Fedorovych HAVRYLYUK, member of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine.

Які туристичні (пішохідні) маршрути проходять через/біля New settler?

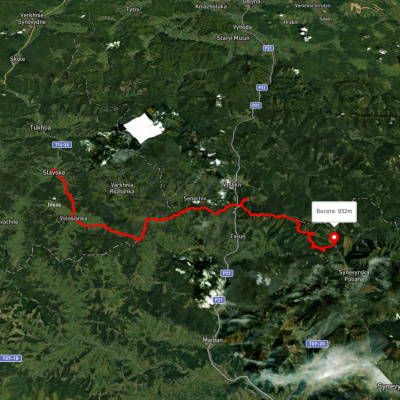

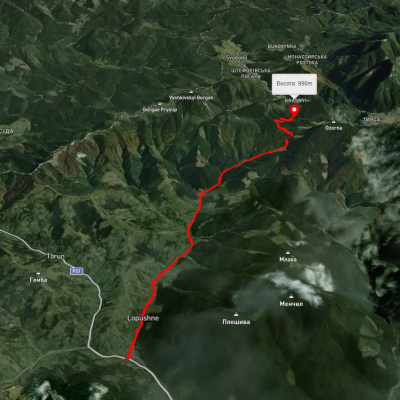

Пропонуємо пройти такі туристичні (пішохідні) маршрути через/біля New settler: с. Славське, через Буковецький перевал до оз. Синевир, с. Лопушне – оз. Синевир, с. Керечки, через г. Стій, г. Великий Верх, г. Гемба, г. Жид-Магура до с. Ричка, Лопушне - Синевир, Східно-Карпатський туристичний шлях, смт. Міжгір'я, через с. Сопки, г. Жид-Магура, г. Гемба, г. Великий Верх до с. Воловець